I’ve been working with JavaScript on and off since the late nineties. I didn’t really like it at first, but after the introduction of ES2015 (aka ES6), I began to appreciate JavaScript as an outstanding, dynamic programming language with enormous, expressive power.

Over time, I’ve adopted several coding patterns that have lead to cleaner, more testable, more expressive code. Now, I am sharing these patterns with you.

I wrote about the first pattern — “RORO” — in the article below. Don’t worry if you haven’t read it, you can read these in any order.

Elegant patterns in modern JavaScript: RORO

Today, I’d like to introduce you to the “Ice Factory” pattern.

An Ice Factory is just a function that creates and returns a frozen object. We’ll unpack that statement in a moment, but first let’s explore why this pattern is so powerful.

JavaScript classes are not so classy

It often makes sense to group related functions into a single object. For example, in an e-commerce app, we might have a cart object that exposes an addProduct function and a removeProduct function. We could then invoke these functions with cart.addProduct() and cart.removeProduct().

If you come from a Class-centric, object oriented, programming language like Java or C#, this probably feels quite natural.

If you’re new to programming — now that you’ve seen a statement like cart.addProduct(). I suspect the idea of grouping together functions under a single object is looking pretty good.

So how would we create this nice little cart object? Your first instinct with modern JavaScript might be to use a class. Something like:

// ShoppingCart.js

export default class ShoppingCart {

constructor({db}) {

this.db = db

}

addProduct (product) {

this.db.push(product)

}

empty () {

this.db = []

}

get products () {

return Object

.freeze(this.db)

}

removeProduct (id) {

// remove a product

}

// other methods

}

// someOtherModule.js

const db = []

const cart = new ShoppingCart({db})

cart.addProduct({

name: 'foo',

price: 9.99

})Note : I’m using an Array for the db parameter for simplicity’s sake. In real code this would be something like a Model or Repo that interacts with an actual database.

Unfortunately — even though this looks nice — classes in JavaScript behave quite differently from what you might expect.

JavaScript Classes will bite you if you’re not careful.

For example, objects created using the new keyword are mutable. So, you can actually re-assign a method:

const db = []

const cart = new ShoppingCart({db})

cart.addProduct = () => 'nope!'

// No Error on the line above!

cart.addProduct({

name: 'foo',

price: 9.99

}) // output: "nope!" FTW?Even worse, objects created using the new keyword inherit the prototype of the class that was used to create them. So, changes to a class’ prototype affect all objects created from that class — even if a change is made after the object was created!

Look at this:

const cart = new ShoppingCart({db: []})

const other = new ShoppingCart({db: []})

ShoppingCart.prototype .addProduct = () => ‘nope!’

// No Error on the line above!

cart.addProduct({

name: 'foo',

price: 9.99

}) // output: "nope!"

other.addProduct({

name: 'bar',

price: 8.88

}) // output: "nope!"Then there’s the fact that this In JavaScript is dynamically bound. So, if we pass around the methods of our cart object, we can lose the reference to this. That’s very counter-intuitive and it can get us into a lot of trouble.

A common trap is assigning an instance method to an event handler.

Consider our cart.empty method.

empty () {

this.db = []

}If we assign this method directly to the click event of a button on our web page…

<button id="empty">

Empty cart

</button>

---

document

.querySelector('#empty')

.addEventListener(

'click',

cart.empty

)… when users click the empty button, their cart will remain full.

It fails silently because this will now refer to the button instead of the cart. So, our cart.empty method ends up assigning a new property to our button called db and setting that property to [] instead of affecting the cart object’s db.

This is the kind of bug that will drive you crazy because there is no error in the console and your common sense will tell you that it should work, but it doesn’t.

To make it work we have to do:

document

.querySelector("#empty")

.addEventListener(

"click",

() => cart.empty()

)Or:

document

.querySelector("#empty")

.addEventListener(

"click",

cart.empty.bind(cart)

)I think Mattias Petter Johansson said it best:

“

newandthis[in JavaScript] are some kind of unintuitive, weird, cloud rainbow trap.”

Ice Factory to the rescue

As I said earlier, an Ice Factory is just a function that creates and returns a frozen object. With an Ice Factory our shopping cart example looks like this:

// makeShoppingCart.js

export default function makeShoppingCart({

db

}) {

return Object.freeze({

addProduct,

empty,

getProducts,

removeProduct,

// others

})

function addProduct (product) {

db.push(product)

}

function empty () {

db = []

}

function getProducts () {

return Object

.freeze(db)

}

function removeProduct (id) {

// remove a product

}

// other functions

}

// someOtherModule.js

const db = []

const cart = makeShoppingCart({ db })

cart.addProduct({

name: 'foo',

price: 9.99

})Notice our “weird, cloud rainbow traps” are gone:

We no longer need new .

We just invoke a plain old JavaScript function to create our cart object.

We no longer need this .

We can access the db object directly from our member functions.

Our cart object is completely immutable.

Object.freeze() freezes the cart object so that new properties can’t be added to it, existing properties can’t be removed or changed, and the prototype can’t be changed either. Just remember that Object.freeze() is shallow , so if the object we return contains an array or another object we must make sure to Object.freeze() them as well. Also, if you’re using a frozen object outside of an ES Module, you need to be in strict mode to make sure that re-assignments cause an error rather than just failing silently.

A little privacy please

Another advantage of Ice Factories is that they can have private members. For example:

function makeThing(spec) {

const secret = 'shhh!'

return Object.freeze({

doStuff

})

function doStuff () {

// We can use both spec

// and secret in here

}

}

// secret is not accessible out here

const thing = makeThing()

thing.secret // undefinedThis is made possible because of Closures in JavaScript, which you can read more about on MDN.

A little acknowledgement please

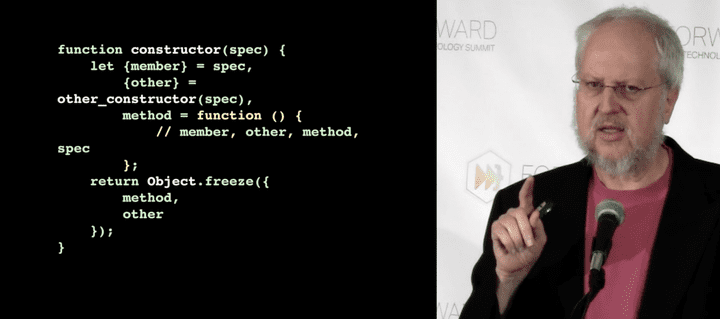

Although Factory Functions have been around JavaScript forever, the Ice Factory pattern was heavily inspired by some code that Douglas Crockford showed in this video. Here’s Crockford demonstrating object creation with a function he calls “constructor”:

My Ice Factory version of the Crockford example above would look like this:

function makeSomething({ member }) {

const { other } = makeSomethingElse()

return Object.freeze({

other,

method

})

function method () {

// code that uses "member"

}

}I took advantage of function hoisting to put my return statement near the top, so that readers would have a nice little summary of what’s going on before diving into the details.

I also used destructuring on the spec parameter. And I renamed the pattern to “Ice Factory” so that it’s more memorable and less easily confused with the constructor function from a JavaScript class. But it’s basically the same thing.

So, credit where credit is due, thank you Mr. Crockford.

Note: It’s probably worth mentioning that Crockford considers function “hoisting” a “bad part” of JavaScript and would likely consider my version heresy. I discussed my feelings on this in a previous article and more specifically, this comment.

What about inheritance?

If we tick along building out our little e-commerce app, we might soon realize that the concept of adding and removing products keeps cropping up again and again all over the place.

Along with our Shopping Cart, we probably have a Catalog object and an Order object. And all of these probably expose some version of addProduct and removeProduct.

We know that duplication is bad, so we’ll eventually be tempted to create something like a Product List object that our cart, catalog, and order can all inherit from.

But rather than extending our objects by inheriting a Product List, we can instead adopt the timeless principle offered in one of the most influential programming books ever written:

“Favor object composition over class inheritance.” – Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software.

In fact, the authors of that book — colloquially known as “The Gang of Four” — go on to say:

“…our experience is that designers overuse inheritance as a reuse technique, and designs are often made more reusable (and simpler) by depending more on object composition.”

So, here’s our product list:

function makeProductList({ productDb }) {

return Object.freeze({

addProduct,

empty,

getProducts,

removeProduct,

// others

)}

// definitions for

// addProduct, etc...

}And here’s our shopping cart:

function makeShoppingCart(productList) {

return Object.freeze({

items: productList,

someCartSpecificMethod,

// ...

)}

function someCartSpecificMethod () {

// code

}

}And now we can just inject our Product List into our Shopping Cart, like this:

const productDb = []

const productList = makeProductList({ productDb })

const cart = makeShoppingCart(productList)And use the Product List via the items property. Like:

cart.items.addProduct()It may be tempting to subsume the entire Product List by incorporating its methods directly into the shopping cart object, like so:

function makeShoppingCart({

addProduct,

empty,

getProducts,

removeProduct,

...others

}) {

return Object.freeze({

addProduct,

empty,

getProducts,

removeProduct,

someOtherMethod,

...others

)}

function someOtherMethod () {

// code

}

}In fact, in an earlier version of this article, I did just that. But then it was pointed out to me that this is a bit dangerous (as explained here). So, we’re better off sticking with proper object composition.

Awesome. I’m Sold!

Careful

Whenever we’re learning something new, especially something as complex as software architecture and design, we tend to want hard and fast rules. We want to hear thing like “always do this” and “ never do that.”

The longer I spend working with this stuff, the more I realize that there’s no such thing as always and never. It’s about choices and trade-offs.

Making objects with an Ice Factory is slower and takes up more memory than using a class.

In the types of use case I’ve described, this won’t matter. Even though they are slower than classes, Ice Factories are still quite fast.

If you find yourself needing to create hundreds of thousands of objects in one shot, or if you’re in a situation where memory and processing power is at an extreme premium you might need a class instead.

Just remember, profile your app first and don’t prematurely optimize. Most of the time, object creation is not going to be the bottleneck.

Despite my earlier rant, Classes are not always terrible. You shouldn’t throw out a framework or library just because it uses classes. In fact, Dan Abramov wrote pretty eloquently about this in his article, How to use Classes and Sleep at Night.

Finally, I need to acknowledge that I’ve made a bunch of opinionated style choices in the code samples I’ve presented to you:

- I use function statements instead of function expressions.

- I put my return statement near the top (this is made possible by my use of function statements, see above).

- I name my factory function,

makeXinstead ofcreateXorbuildXor something else. - My factory function takes a single, destructured, parameter object.

- I don’t use semi-colons (Crockford would also NOT approve of that)

- and so on…

You may make different style choices, and that’s okay! The style is not the pattern.

The Ice Factory pattern is just: use a function to create and return a frozen object. Exactly how you write that function is up to you.